Private Bodies vs. Global Bodies

Reflecting on numerous disability studies theories that we have covered in the course so far, Tobin Siebers attempts to define bodies and bodily idenitities as positioned within the social and political environment. I find it particularly interesting how Siebers juxtaposes identities defined through race or gender, and identities defined through a disability. As his definition clearly denotes, “It is true that some individual bodies are black, female, or both, but the social meaning of these words does not account for everything that these bodies are. Rather, these words denote large social categories having an interpretation, history, and politics well beyond the particularities of one human body. This fact is, of course, largely recognized, which is why the attempt to reduce a given body to one of these terms carries the pejorative label of racist or sexist (Siebers, Disability Theory: Corporealities Discourses of Disability, 80). When it comes to defining a body through ability/disability, that is a completely different story. If a person is in a wheelchair, or if they are deaf, then their body is defined by nothing else but their inability to move or hear. As a result,” disability does not yet have the advantage of a political interpretation because the ideology of ability remains largely unquestioned “(Siebers 81). In the age when humans are exposed to more danger and more accidents, and where our bodies are becoming more susceptible to different illnesses, how can we define ability? What lexicon defines and determines ability? Is an ability that which is opposite from a disability? Siebers opens up a completely new persepctive, stating that disability is defined by a social and built environment, rather than by medical terminology or society itself. When I think about it, the way houses, buildings, restaurants, cafés, or shopping malls are designed—in general, the way society designs spaces—is very delimiting to people with disabilities. The society favours only one form or aspect of the human body, and due to that, it defines the characteristics of one’s social body. ‘This social body determines the form of public and private buildings alike, exposing the truth that there are in fact no private bodies, only public ones, registered in the blueprints of architectural space’” (Siebers 85).

- If there are no private bodies, as Siebers claims, then can we really be “slaves to our own bodies” (heeding Hegel’s and Socrates’ definition), or are we simply slaves to the social spaces constructed by human bodies?

- Can public spaces be disabling. i.e can their functions become limited/limiting?

Picture 1: “Bodies in Urban Spaces”, a performance designed by an art director Will Dorner, who is interested in the ways bodies can be used to fill empty spaces, in particular empty urban spaces. What makes this performance particularly interesting is that it does not only include professional dancers and performers. Passers-by also volunteer to take part in this act.

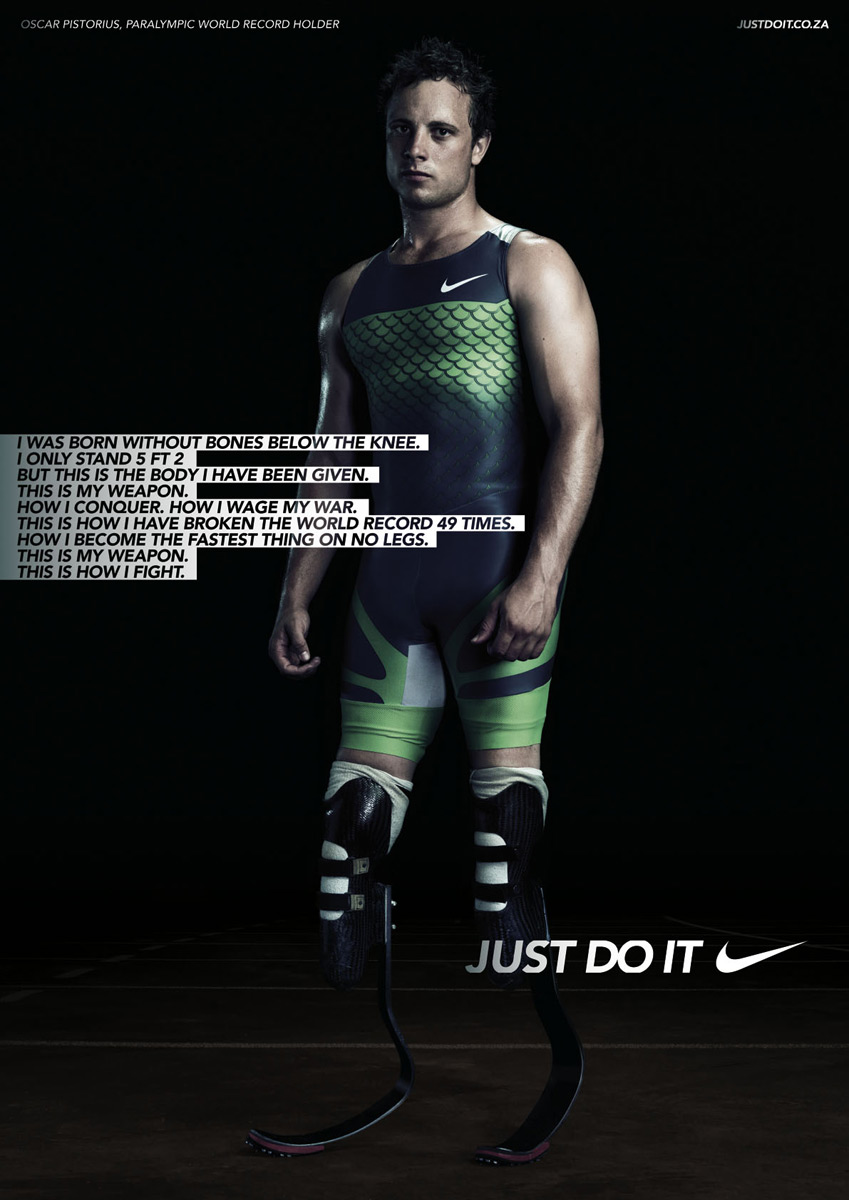

Picture 2: South-African runner Oscar Pistorius in a commercial for Nike.

In the final chapter of his book Crip Theory, Robert McRuer places his focus on the location of bodies in a global world, and on a world as inhabited by global bodies. If disability studies has gone global, the question is whether that “gloability” pertains solely to the United States, Canada, and most of Europe, or whether it also addresses the rights of disabled people in Third World countries? Interestingly, we do not seem to hear much about disability rights movements and disability rights activists in such countries, partially because the media mainly broadcasts the negative aspects of Third World societies, and even if there are any positive things happening in the development of disability rights activism, we cannot know that. If we look at global bodies as constructs that “inhabit and move between global cities” (McRuer 203), then most individuals in Western or Westernized societies possess global bodies indeed. Some of us travel between cities for work; international students travel between their home city and the city in which they live during their studies; people involved in long-distance relationships travel between one city to another to see their partner. However, McRuer also implies that global bodies may not necessarily refer to humans. On the contrary, “twentieth-century modernity established global bodies such as the League of Nations and the United Nations; the age of Empire has privileged more diffuse global bodies such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and—of course—multinational corporations” (203). Tangible, human bodies have become dependent on financial and multinational corporations to such an extent that the possibility of nurturing, moving, or improving our bodies depends on our ability to afford and use the products of these corporations. We are now trapped in the age when our bodies have turned into what Grace Chang calls “disposable domestics” (referenced in McRuer, 203). I really like how McRuer highlights the fact that financial coprorations have contributed to creating a predominantly female, migrnat workforce, which can be seen in the cases of many big corporations, such as McDonald’s, Wal-Mart, Benetton, Adidas, Nike, and so on. McRuer gives an example of Wal-Mart, which oftentimes uses people with disabilities in their commercials, but in reality they do not want to hire anyone who does not fit within their image of an able-bodied person. This made me think of Nike, and the ways they promote their products in commercials. Just like in Wal-Mart’s commercials, it is not uncommon to see people with disabilities in the commercials for the Nike company. Nike, no doubt, has very inspiring commercials with strong messages of encouragement and motivation for its viewers, from both able-bodied and disabled communities. Some of the messages we get in the commercials are: “My body is my weapon… This is how I defeat my enemies, how I make victory mine.”, “I’ve got soul but I’m not a soldier”, or “I don’t want to be a superstar… I don’t collect the titles, I collect hours of hard work and pain… I don’t want to be a superstar. I want to be better than that—I just want to be me!” What we can discern from these messages is that they are directed at the human body and its possibilities, the strength of mind, and the ability to win stereotypes over what one’s body is capable of. Unfortunately, in the world outside the commercials, the Nike company operates in a completely different way, by exploiting female workers, children, and people with disabilities to craft shoes and other clothing items. On top of that, these workers are usually people from Third World countries, working in sweat shops in China, Vietnam, or Indonesia and getting less than a dollar a day for the incredible amount of work. The Nike company, just like Wal-Mart, does not have any disabled persons hired in their main offices in the United States or Europe; however, commercials made in the spirit of equality, tolerance and motivation reach a vast number of their viewers, resulting in hundreds of millions of income for Nike each year.